Warning: rambling. -Ed.

It’s common, in trope-y writing, like horror or sci-fi, to intentionally make the reader feel a certain horror in or about their own body. This can also come up in authors who inhabit the ‘weird’ spectrum, like Borges or Murakami.

The thing about this is that it’s so easy. All I have to do is point out that you have a body.

We don’t like to think of ourselves as inhabiting a body. This comes in many flavors. Dualism is an extremely popular one. Your body is separate from your you. Your soul, your spirit, your whatever-you-want-to-call-it: your mind is not a part of your body, so your mind is not made of meat. Things made of meat are gross. We eat things made of meat. But your mind, which you’ve managed to separate from your body just by thinking about it (thinking is magical!), is still, you know, physically bound to your body. You can’t go anywhere that your meat doesn’t let you. You’re born meat, and you die meat.

Gross, right?

Now, there’s a second aspect to this. Bodies die. So we come up with elaborate mechanisms for which our bodies might die, but not us, not really. Dualism is a very strongly held belief in basically every school of thought, even atheism. So it’s not just that meat is gross–meat is mortal, too. Like I said, a lot of us eat it every day without really giving it a second thought. Any notion that your you-ness is all tied up in this meat nonsense is horrifying.

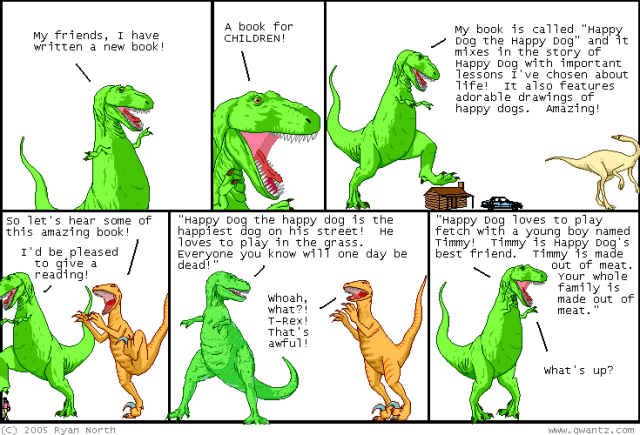

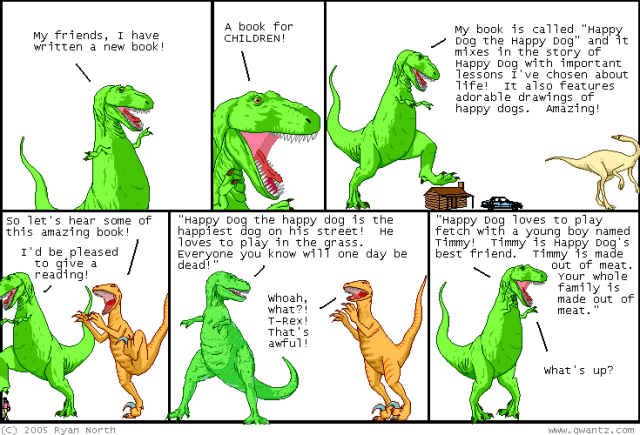

So how can I make sure you feel this? First, I can just tell you. You are mortal. You are made of meat. Like in this hypothetical children’s book from the inimitable Ryan North:

Or this gem, which Neal Stephenson sort of randomly plops down in the middle of a scene in Cryptonomicon:

The room contains a few dozen living human bodies, each one a big sack of guts and fluids so highly compressed that it will squirt for a few yards when pierced. Each one is built around an armature of 206 bones connected to each other by notoriously fault-prone joints that are given to obnoxious creaking, grinding, and popping noises when they are in other than pristine condition. This structure is draped with throbbing steak, inflated with clenching air sacks, and pierced by a Gordian sewer filled with burbling acid and compressed gas and asquirt with vile enzymes and solvents produced by many dark, gamy nuggets of genetically programmed meat strung along its length. Slugs of dissolving food are forced down this sloppy labyrinth by serialized convulsions, decaying into gas, liquid, and solid matter which must all be regularly vented to the outside world lest the owner go toxic and drop dead. Spherical, gel-packed cameras swivel in mucus greased ball joints. Infinite phalanxes of cilia beat back invading particles, encapsulate them in goo for later disposal. In each body a centrally located muscle flails away at an eternal, circulating torrent of pressurized gravy.

Isn’t that fun? In the first example, North just points out some meat and mortality; in the second, Stephenson makes it super gross. They’re not especially horrifying, I suppose, but they certainly make me nervous and a little squicked out, which is the point.

One thing that is horrifying, in its own special way, is a sci-fi short story (and a wonderful short film version) that does just this (linked above as well), in which the fact that we’re made out of meat is described from the point of view of somebody who is just now discovering that it’s even possible for something sentient to be made out of meat:

“They’re made out of meat.”

“Meat?”

“Meat. They’re made out of meat.”

“Meat?”

“There’s no doubt about it. We picked up several from different parts of the planet, took them aboard our recon vessels, and probed them all the way through. They’re completely meat.”

“That’s impossible. What about the radio signals? The messages to the stars?”

“They use the radio waves to talk, but the signals don’t come from them. The signals come from machines.”

“So who made the machines? That’s who we want to contact.”

“They made the machines. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. Meat made the machines.”

“That’s ridiculous. How can meat make a machine? You’re asking me to believe in sentient meat.”

“I’m not asking you, I’m telling you. These creatures are the only sentient race in that sector and they’re made out of meat.”

[…]

This upsets the aliens enough that they decide to declare the sector uninhabited, erase all records of humanity, and move on. Later, they muse about how lonely it must be, thinking you’re alone in the universe, except they’re talking about an intelligent crystal or something or other.

So, in order to make you feel weird about your body (which is of course all you are and ever will be), I can:

- Remind you that you’re mortal

- Describe your body in excruciating detail

- Talk about your body as though I’d never seen a body before

And we haven’t even gotten to the part where I have you imagine anything even happening to your body. All of these examples so far are just descriptive.

In Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, one of the characters has a scar on her face and something wrong with her leg. He tends to mark his characters like this. In 1Q84 one of them has a weird ear. Body marking is also very important in the Germanic epics and sagas. This is the realm of injuries and minor mutilations. It sets people apart as different, or important, or both. That’s all another post though.

For now, man, how weird is it that you have a body?